How to Be a Refugee Read online

SIMON MAY

HOW TO BE A REFUGEE

ONE FAMILY’S STORY OF EXILE AND BELONGING

With inexpressible gratitude to Marianne, Ursel,

and Ilse – my mother and my two aunts; to my grandfather

Ernst and great-uncle Theo, who died long before I was born,

but whose lives have inspired and challenged me since childhood;

and to my beloved father Walter and my grandmother Emmy,

both of whom I knew only briefly.

CONTENTS

Principal Characters

List of illustrations

Foreword

Introduction: Death at the German Embassy

PART I

A BERLIN IDYLL: 1910–1933

1. Blumeshof 12

2. ‘Musician must always look beautiful’

3. Where Germans and Jews secretly met

4. Ernst’s conversion

5. ‘Get out of here immediately, you East-Asian monkey’

6. The operation on Lenin

7. The hopeful case of Moritz Borchardt

8. Ernst’s death

PART II

THREE SISTERS, THREE DESTINIES: 1933–1945

9. Next stop: Catholicism

10. ‘Life is continually shedding something that wants to die’

11. Great-uncle Helmut: priest, philosopher, boxer

Ursel’s World: The Aryan Aristocrat in Hiding

12. From the Liedtkes to the aristocrats

13. Ursel becomes an Aryan

14. Ursel becomes a countess

15. The Gestapo comes calling

Ilse’s World: Fearless in Berlin

16. Dancing at Babelsberg

17. Ilse, Christabel, and the ‘submarines’

18. The Rosenthals and their guest

19. How did Ilse do it?

Marianne’s World: An Immigrant in London

20. Stateless at the German Embassy

21. The past cannot be predicted

22. Czech mates

23. Grandmother Martha May

24. Saved by arrest

PART III

NEWLY CREATED WORLDS: 1945–1990

25. C & A to the rescue

26. Locked in the attic

27. Ilse returns to Berlin

28. Geri and Eva are shot

29. ‘I love shopping’

30. Ilse’s Nazi flag business

31. Chaplain Sellars

32. Ilse in the parsonage

33. The Jewish altar server

34. The promised land of Switzerland

35. Central Europe in London

36. Hiding the crucifix

37. Banished to the car

38. The European Union as saviour

PART IV

THE PAST CANNOT BE RESTITUTED: 1990–

39. Love declaration to Germany

40. The blessings of procrastination

41. Did Great-uncle Theo have another life?

42. The Nazi and the Jewish woman

43. Just ask the Führer

44. The Jew and the ex-monk

45. The parrot and the bulldog

46. Lech Wałęsa, the ‘Jewish President of Poland’

47. Finding Grandfather May

48. The Jewish cemetery of Trier

49. The survivor file

50. We have Saddam Hussein to thank

51. The file goes astray

52. Finding the heirs

53. Pip

54. The missing 1 per cent

55. The Aryanizers demand compensation from us

56. How to have a good war

57. ‘Progress!’

58. The elusive share certificate

59. Restitution? No, thanks

60. Romeo in Bayreuth

61. Mother’s last ‘last visit’ to Berlin

62. Mother’s death – My ‘return’ to Germany begins

63. A devastating discovery

64. The woman and the dandy

65. A London club

Coda: Dinner at the German Embassy

Acknowledgements

Notes

Sources

[E]verything must be earned, not only the present and future, but the past as well . . . and this probably entails the hardest work of all.

Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena1

‘That was your father you found. You’ve been carrying your father’s bones – all this time.’

Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon2

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

Relationship to the author is shown in brackets

ERNST LIEDTKE, 1875–1933 (maternal grandfather): born Christburg, then in West Prussia. Lawyer; husband of Emmy; father of Ilse, Ursel, and Marianne. Converted from Judaism to Protestantism. Died in Berlin after being expelled from his profession in April 1933 under the Nazi ban on non-Aryan lawyers.

EMMY LIEDTKE, 1890–1965 (maternal grandmother): born Emmy Fahsel; wife of Ernst and mother of Ilse, Ursel, and Marianne. Lived in Germany all her life. Converted to Catholicism.

THEODOR LIEDTKE, 1885–1943 (maternal great-uncle): brother of Ernst Liedtke; uncle of Ilse, Ursel, and Marianne; salesman at Tietz department store in Berlin; deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1942, and from there to Auschwitz.

HELMUT FAHSEL, 1891–1983 (maternal great-uncle): Catholic priest and philosopher. Left Germany in 1934 for Switzerland on a tip-off from Franz von Papen, Hitler’s deputy chancellor. Apart from a brief spell in Germany after the war, spent the rest of his life in Switzerland.

ILSE LIEDTKE, 1910–1986 (older maternal aunt): photographer who spent the war in Berlin. Lover of Harald Böhmelt, composer and Nazi Party member. Except for a few years in Kiel from 1948, she lived in Berlin all her life. Converted to Catholicism.

URSULA (URSEL), COUNTESS VON PLETTENBERG, 1912–1995 (younger maternal aunt): born Ursula Liedtke. Actor who became a Catholic; secured ‘Aryan’ status in 1941 with the help of Hans Hinkel, a senior official in Hitler’s regime; married Franziskus, Count von Plettenberg in 1943; fled to the Netherlands in 1944; returned to Germany soon after the war and lived there for the rest of her life.

MARIANNE MAY, 1914–2013 (mother): born Marianne Liedtke. Violinist, stage name Maria Lidka; emigrated to London in 1934; married Walter May in 1955. Converted to Catholicism.

FRANZISKUS, COUNT VON PLETTENBERG, 1914–1968 (maternal uncle by marriage): married Ursel in 1943; deserted the German army in the Netherlands in 1944 and went into hiding with Ursel.

WALTER MAY, 1905–1963 (father): born in Cologne. A banker and then a brush manufacturer; emigrated to London in 1937. His first wife Hilde May was also a cousin; his second wife was Marianne Liedtke.

EDWARD MAY, 1903–1968 (paternal uncle): born in Cologne. Doctor, amateur cellist, and master chef; emigrated to London in 1934.

KLAUS MELTZER, 1943–2017 (putative cousin): claimed to be a grandson of my great-uncle Theodor Liedtke. Son of Ellen Liedtke and Nazi Staffelkapitän Walter Meltzer. Lived in Cologne. Photographer; painter; educationalist; founded a community centre for Turkish women.

ELLEN LIEDTKE, 1919–1971: putative daughter of Theodor Liedtke, whom Ernst, Emmy, Marianne, Ursel, and Ilse all believed to be a childless bachelor.

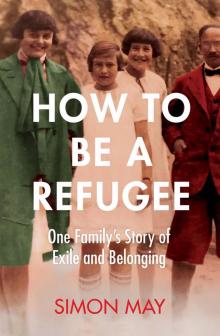

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. My maternal grandparents and their three daughters on holiday in the Swiss Alps in the mid-1920s. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass.)

2. A room in my grandparents’ Berlin apartment at Blumeshof 12. (Ibid.)

3. Ernst’s certificate of his exit from Judaism in 1910. (Ibid.)

4. Ernst’s certificate of baptism, 1910. (Ibid.)

5. Ernst and his brother Theo sailing from Bremen to New York on board the Kaiser

Wilhelm II in 1909. (Ibid.)

6. Marianne, Ursel, Ilse. Berlin, 1917. (Ibid.)

7. Ernst and Emmy on the North Sea island of Helgoland in 1926. (Ibid.)

8. The Liedtkes’ boat on the Wannsee. Ernst in the peaked cap, Emmy next to him and Ilse to the left of the gangplank. (Ibid.)

9. The final page of Marianne’s concert and theatre notebook, in April 1933, with performances by Wilhelm Furtwängler and the quartet of her violin teacher, Max Rostal. (Ibid.)

10. Ilse. (Ibid.)

11. Ursel. (Ibid.)

12. Marianne. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass. Photo: Ilse Liedtke.)

13. The three sisters as teenagers. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass.)

14. Marianne and Ursel playing violin and accordion with canine audience. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass. Photo: Ilse Liedtke.)

15. Ursel and probably Katta Sterna in a Berlin cabaret. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass.)

16. Ursel, Emmy, Ernst and Marianne having tea on their boat. (Ibid.)

17. Ilse and her boyfriend, Harald Böhmelt, at the Trichter dance hall on Hamburg’s Reeperbahn, late 1930s. (Werner Finck, Witz als Schicksal – Schicksal als Witz. Marion von Schröder Verlag, Hamburg, 1966, p. 60.)

18. Ellen Liedtke, putative daughter of Theo Liedtke, and her fiancé, Walter Meltzer, in 1939. (Archive of Simon May. Gifted by the late Klaus Meltzer.)

19. Walter Meltzer with comrades in Nuremberg during the 1933 Nazi Party rally. (Ibid.)

20. Ursel with Maria ‘Baby’ von Alvensleben, probably Lexi von Alvensleben, and their mother, Countess Alexandra von Alvensleben, at the yacht club Klub am Rupenhorn, Berlin, 1931. (ullstein bild Dtl. / Contributor)

21. My mother, Marianne, with violin. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass. Photo: Ilse Liedtke.)

22. Marianne playing in a wartime concert at the National Gallery in London. On the reverse of the photo she writes: ‘The concert was moved to the basement as a bomb had just fallen upstairs.’ (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass. Photo: Erich Auerbach)

23. A Czech Trio programme from 1941. The Trio was sponsored by the Czech government-in-exile in the UK and provided my mother’s first legitimate earnings as a refugee. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass.)

24. Ursel’s letter of thanks, dated 17 July 1941, to SS officer Hans Hinkel, who was key to her achieving Aryan status. (Bundesarchiv Berlin. BArch, R9361V/56771.)

25. The resident’s cards on Ursel in Bremen City Hall, 1931–43. (Staatsarchiv Bremen. StaB 4,82/1 – 0909, Bild 231 und StaB 4,82/1 – 1185, Bild 278. Einwohnermeldekarten der Stadt Bremen für Ursula Liedtke.)

26. A letter of 17 September 1943 from Count Franziskus von Plettenberg’s military commander permitting him to marry Ursel and enclosing his medical certificates and proof of Aryan origin. (Bundesarchiv – Abteilung Militärarchiv, Freiburg im Breisgau; BArch, PERS6/158762, ‘Heiratsgenehmigung für Hptm. (Tr.O.) Graf von Plettenberg (Franz)’ erteilt vom ‘Höheren Kommandeur der Flakausbildungs-und Flakersatzregimenter’, 17 September 1943.)

27. The bombed idyll of Blumeshof 12 in 1945. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass. Photo: Ilse Liedtke.)

28. The ruins of Ilse’s studio at Budapesterstrasse 43, Berlin, in 1945. (Ibid.)

29. Ilse’s temporary studio in 1945, with her portraits of US soldiers. (Ibid.)

30. The temporary graves of Geri and Eva, Ilse’s neighbours, shot in their home by Soviet forces and buried by her, Berlin, 1945. (Ibid.)

31. My father, Walter May, in London in 1958. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass.)

32. My mother, Marianne, my brother, Marius, and me in 1959/1960. (Marianne Liedtke-May’s Nachlass. Photo: Marianne Samson.)

FOREWORD

The most familiar fate of Jews living in Hitler’s Germany is either emigration or deportation to concentration camps. But there was another, rarer, and today much less well known side to Jewish life at that time: denial of your origin to the point where you manage to erase almost all consciousness of it. You refuse to believe that you are Jewish. In reaction to a long history of racial and religious persecution, and out of intense love for German culture, you repudiate your birthright.

This feat of repudiation, epitomized by my mother, her sisters, and her parents, did not originate with Hitler’s rise to power. The ground for it was prepared long before, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when some Jews, such as Rahel Varnhagen – the great woman of letters, whose extraordinary intellect and sensibility were admired by Goethe, Schiller, and Wilhelm von Humboldt, among other luminaries of her time – came to regard their heritage as a curse that poisoned their whole existence and debarred them from full belonging in the world of German culture, to which they were so fervently devoted.

But in my mother’s family such repudiation of origins was pushed to an extreme, becoming an ethnic purging of the inner world – a profound alchemy of the soul. Nor did it cease with Hitler’s defeat. Though my mother had fled to London from Nazi Germany and I was born well after the war into a vastly more tolerant era, I was forbidden to think of myself not only as Jewish but now also as German or British.

I have attempted to tell the story of the extraordinary German-Jewish world from which my family came – as well as of my own quest to carve a path to both its heritages – principally through the remarkable lives of three sisters: my mother and my two aunts. Their very different ways of grappling with what they experienced as a lethal origin included conversion to Catholicism, marriage into the German aristocracy, securing ‘Aryan’ – non-Jewish – status with high-ranking help from inside Hitler’s regime, and engagement to a card-carrying Nazi under whose protection survival in wartime Berlin was possible. But we also meet other figures with a similar heritage, such as my maternal great-uncle, who became a Catholic priest and translator of St Thomas Aquinas; and the love child of a Jewish woman and a passionate Nazi, who, so far unknown to us, claimed me and my family as his sole surviving relatives.

To recount these contortions of ethnic and cultural concealment is – categorically – not to criticize them. Who are we who have never experienced racial hatred in its vehement forms, let alone in the form of state-sanctioned persecution, to criticize anyone’s strategy to survive and flourish in such conditions? Who are we who have lived free lives where our particular heritages have been accepted and sometimes even admired, to cast judgement on ancestors who were forced to find ever more ingenious ways of appearing harmless to the majority – and to themselves? Their choices are only my business because to be born into this strange tributary of the Jewish experience was to be commanded to construct an identity out of everything that I was not. Following the early death of my father, also a German-Jewish refugee, I was raised a Catholic and mandated, on pain of betraying my mother and her parents, to live as a refugee in the country of my birth. In effect, I was instructed never to arrive anywhere: to be a hereditary refugee.

The urgent questions that this raised for me – questions of identity and belonging that seem to be everywhere around us today – are these: Are we not all in some way exiles in an era that is shedding its past at unprecedented speed? Can the worlds we have lost be restituted, even if minimally, along with their rich networks of meaning, without fruitless, and possibly self-destructive, efforts to set the clock back? Or is all restitution a pipe dream: are lost worlds necessarily the unattainable territory of ghosts who powerfully inspire our lives from a great distance, but with whom we can never live or speak again? Either way, how many generations can it take for a refugee family to feel at ease in their adopted country, no longer pining for a place from which they were once uprooted? And at a time when identity is becoming a choice rather than just a given, will it get easier – or harder – to be a refugee?

INTRODUCTION

Death at the German Embassy

i.

It was only after my mother departed for England that I discovered the circumstances of my father’s death.

I was eleven yea

rs old and finishing dinner with my mother’s two sisters, Ursel and Ilse, both of whom had come from Germany, where they lived, to spend the summer holiday with us in the Swiss Alps. We were sitting in the kitchen of our rented chalet in the hamlet of Gsteig, nestled in a corner where one valley makes a sharp, ninety-degree turn into another. Ilse had whisked the plates from the table and was already scrubbing them before I’d finished eating. Wherever Ilse was, German orderliness reigned. Outside, the sun was sinking behind the glaciers, turning them a brilliant pink, and I could hear the owners of our chalet pottering about in their vegetable garden and the occasional shot from a nearby rifle club, when Ursel said to me, apropos of nothing, ‘Simon, do you know how your father really died?’

Shock at Ursel’s abrupt summoning of a loss that I had no idea how to grasp struggled, almost at once, with guilty euphoria at hearing his name. What a wonderful question to ask me! ‘Do you know how your father really died?’ My father had collapsed, out of the blue, when I was six, and had been buried in silence. He’d been present at breakfast; then left the house and never returned.

I wasn’t taken to the funeral on the grounds, I later learned, that this would be traumatic for a child. But I prayed for him at least once a week, hoping that he would be happier as a result, and that speaking to God would also be a way of speaking to him, even if he couldn’t answer me back; but doubting that it could be that simple.

The silence was echoed by his almost total absence from our home. Nothing personal of his remained: no tie, or pair of shorts, or book that he’d marked up, or love letter, or the silver cigarette case that my mother told me she had given him for the birthday on which he had finally decided to quit smoking. I had rummaged through cupboards and drawers many times looking for a relic of his life. But everything had been cleared out.

Everything except for the magnificent drawings and lithographs on the walls of our living room. These emblems of his life should have been my link to him. Instead they were mocking reminders of his absence; ghostlike markers of a presence that was no more – their own life frozen when they lost the person who chose them and of whose striving they spoke. Since childhood I have found the idea of inheritance peculiarly burdensome – tolerable only if we, the living, have justified it through an understanding of this person’s relation to what they have bequeathed us, and gratitude for the effort they invested in acquiring and caring for it.

How to Be a Refugee

How to Be a Refugee